When the school year started in September 1967 my honorary aunt Joan ‘The Bone’ Byrne took up her post at Hong Kong’s Wellington College in Caine Road and I began my undistinguished academic career at Kennedy Road Junior School.

It was a steep learning curve for us both.

Wellington College was a private English language school for middle class Chinese. The college was owned by a millionaire who spoke no English and owned four such establishments, according to Joan who was engaged to teach English and ‘oral,’ which I don’t believe had the same connotations in 1960s Hong Kong as it does today.

Salary was by negotiation and there was no sick pay. In fact, not only was there no sick pay, teachers who had to take a day off were required to find and pay for their own replacement.

Each class had 49 students, all referred to by number rather than name. Legally there should have been only 45 students, so when an inspector came, students 46, 47, 48 and 49 got up and moved desk and chair to the landing, in full view of the inspector, Joan said.

“We were given instructions on what page of what book to teach each day and material was rote learned and regurgitated to ensure exam results to encourage enrolment of a full complement of students.

“I found out later that there was a student in each class who recorded whether or not you had covered the required material. I used to do the required task in the first 15 minutes then do my own thing for the remaining 35 minutes.”

There were no playgrounds. School was in two sessions, a morning session from 8am to noon six days a week, followed by an afternoon session from 1pm to 5pm, with a completely new class of students.

Joan worked the morning session and part of the afternoon session to build up her finances, teaching in all some 800 students each week. She remembers an amah coming to the school and physically feeding her young charge his lunch.

She also recalls the janitors, one for each floor at the college, who worked there during the day and slept on the staffroom floor at night.

Your young Girl Reporter was having a very different educative experience at Kennedy Road Junior School, just down the road from our flat in Grosvenor House. If I was lucky I got a lift to school from one of the pak pai drivers who served our building.

A pak pai was a private limousine which could be booked by our middle class residents who wanted to make a splash.

The drivers congregated between jobs in the management office and it was always worth a little detour before I left the building to see if Ah Lung was up for giving me a lift to school in his Mercedes.

My school day started at the usual hour, with lessons beginning at 9am and lasting until 3pm. Every so often they would play around with the hours. One year we finished at noon but attended on Saturday mornings, which sounds more in line with the Chinese school where Joan taught.

The main school building had a Dickensian air with dark wood panelling in the stairwells and high walls in the classrooms painted institutional grey.

They must have been recently done, or perhaps it was the humidity, but the walls always seemed tacky to the touch and had a rather sickly smell.

Each year had two classes, with the youngest years clustered around a courtyard dominated by a magnificent camphor tree and, more importantly, a Wendy house.

On my first day, I was the only kid who hadn’t brought a snack tor the mid-morning break. The next day, having explained the problem to Grandma, I was equipped, like the others, with a little pack of biscuits.

But instead of allowing me to sink back into obscurity, my morning tea only provoked more curiosity, as no-one seemed to have ever seen Vegemite on crackers before.

Our teacher took us around the school one day to point out some of its features and what they meant. Before that, the stone lions and altar in the playground were merely a backdrop to the latest game craze – whether it was something relatively harmless like marbles or the seriously dangerous, like Clackers.

But that day Mrs Crosbie told us that the little shrine fenced off from clambering kids was in fact Japanese, as was the rising sun etched into the gable of the school’s second building, known as the Annex.

As I remember it, she said the building was either Japanese headquarters or a hospital during the Second World War and I had always assumed those features were added then. In fact the old building was built in around 1918 as a Japanese school for 80 students so it’s more likely they were there from the outset.

Presiding over all she surveyed was Miss Holmes, the formidable headmistress who had been teaching at Kennedy Road Junior School since it opened in 1961 to meet the demands of a growing expatriate population.

She was still principal when the school moved to new premises in Sandy Bay in 1989.

At Wellington College Joan was frustrated at first. “I would look at the class, see 49 black-haired students, heads down over their books, writing down every word I said. No names, just numbers.

“I would ask a question and get no response. All were afraid of making a mistake,” she said.

“I well remember the occasion when I had asked a question four times without response. I turned my back and exclaimed loudly “Ai Yah.”

The class laughed. Apparently I had used, in my perfect barroom accent, a rather slang-ish expression not usually used by Europeans.”

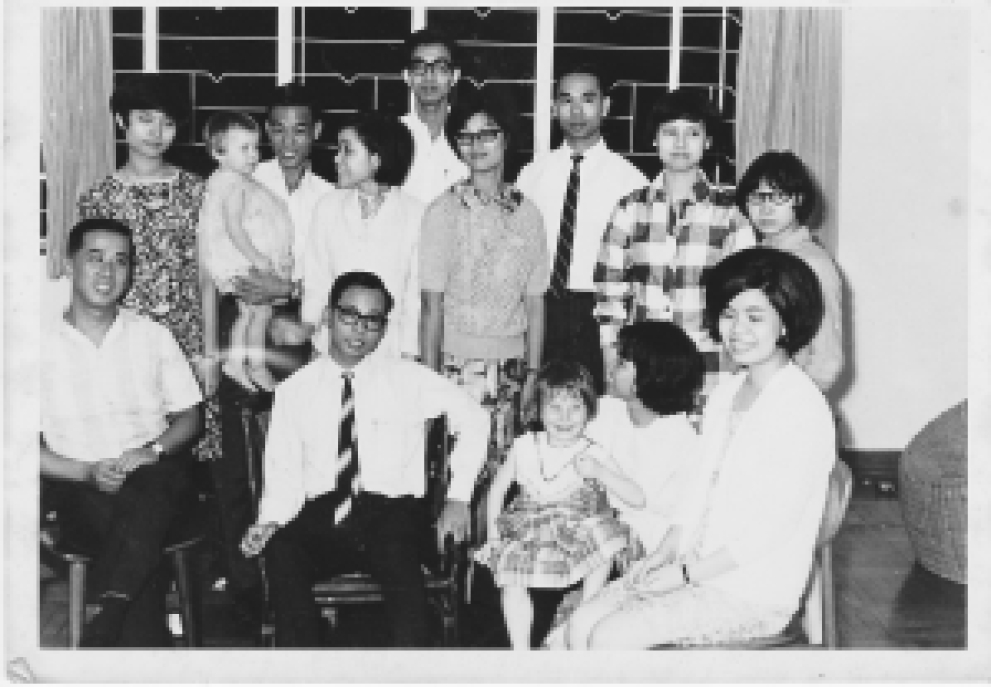

With the ice broken, a group from this class – Form IV C – soon joined the regular visitors to our flat in Macdonnell Road. They first started coming over for extra oral lessons and in January 1968 formed a social club, helped along with a donation of 10 dollars from Joan to organise out-of-school activities.

The Permanent Club, as they called themselves, included two Josephs, Patrick, Danny, Betty, Alfred and Florence but they would often change their English names which could lead to confusion.

Joan remembers coming home on a ferry with the group and playing the game ‘who stole the cookie from the cookie jar.’ “One student missed his name and when challenged his excuse was that he’d changed it the week before,” she said.

Many of the Permanent Club stayed in touch with Joan and she still has the letters they wrote to her. They also remained good friends to us over the years and were frequent visitors to Grosvenor House after she left Hong Kong.

Their homes were small and our flat was huge, with occupants who loved a houseful, so when the Permanent Club wanted to throw a birthday party for Danny they held it at our place.

Joan was in Switzerland when one of the Josephs – who was briefly charged with the thankless task of trying to teach me Cantonese during the summer vacation – wrote to her:

“As time goes by I often pay visit to Jack’s family with some of our classmates, eg Danny, Patrick, Alfred.

“Last month we even borrowed Jack’s house to hold a birthday party for Danny.

“About 70 guests were invited on that day and we played until midnight. Mr and Mrs Spackman also joined this party.”

The Permanent Club remained firm friends of ours for many years. My memories are peppered with ferry rides to Cheung Chau – where Alfred lived – or to Silvermine Bay on Lantau, to hire bicycles and stay in a hostel right on the beach, a huge hall with a gap running over the partitioned sleeping areas, giving plenty of flying space to the nesting swallows which filled its eaves.

On the ferry we sat cross-legged on the back deck singing songs from the latest Hit Parade – a little local publication with all the song lyrics and guitar chords of that week’s chart toppers. In typical Hong Kong fashion, it would hit the streets almost as soon as the American charts came out.

Joan, meanwhile, was on her way to England. She had a promise to keep, to her grandfather William Joseph who was known to the family as ‘Father’ Byrne.

He was 12 years old when he last saw his young brother, left behind when the family was split up following the death of their father. Young Bill and his 13-year-old sister were sent unaccompanied to an aunt in Australia. Other siblings went to family in Ireland while the two youngest children had remained in England with their mother.

When Joan left us in 1969 it was to fulfil her promise to meet the family, in particular that young brother that her grandfather had left behind more than 70 years earlier. As you would expect from my extraordinary aunt, she took the long way round. But that’s a story for another day.

© Maria Spackman 2017

This is the latest in a series of posts chronicling the adventures of my extraordinary aunt, who spent two years as a teacher in Hong Kong before resuming her travels. You can read more of her story here:

My Extraordinary Aunt: Taking the long way to London – before she joined us in Hong Kong, Joan travelled through Asia.

My Extraordinary Aunt: In the shadow of Lion Rock – Joan arrived in Hong Kong in May 1967, where working conditions were about to lead to one of the most turbulent times in its history.

Hong Kong 1967: So you say you want a revolution – Hong Kong, May 1967. There was a riot going on.

5 Trackbacks / Pingbacks